It Feels Like Plan B to Me

'Tis the season for prognosticating. Here's what could happen next with independent-contractor policy in New Jersey and the nation.

I know, I know. It’s a bit dicey to offer predictions for 2026 at this time of year. Anything can happen, and everything can change faster than a Pro Bowl NFL kicker missing a short field goal and an extra point in the same game (I’m looking at you after Saturday’s special teams meltdown, Cameron Dicker).

With that big, fat caveat—really, anything can happen—I’m looking across the field of play for independent-contractor policy at the end of 2025, and I’m seeing quite a few signs that all seem to point in the same direction when it comes to what might happen next.

We may be about to experience a nationwide reset on the type of policy we’re going to have to fight as independent contractors. There’s a solid chance that this reset may come to my home state of New Jersey next, followed by Congress and the U.S. Supreme Court.

Here are all of the reasons why.

Reclassification was Plan A

Back in September 2024, I published this Q&A with Glenn Spencer of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. We talked about what was, at that time, a new Chamber report. It detailed the fact that a generation ago, labor unions were private, voluntary groups that organized workers and bargained collectively, while today, unionists have a different tactic. They lobby to achieve their agendas through the government.

We also talked in that Q&A about ways that union organizers were trying to use political clout to gain legal access to all kinds of independent contractors.

Spencer told me:

“Unions are a business, and dues are the income for that business. So like any other business, they will pursue revenue opportunities using multiple strategies.”

Multiple strategies, indeed—and we don’t have to guess what they are. Years before my conversation with Spencer, four unionist members of Congress laid out their strategic policy ideas in this 2018 report. It details, among other things, ideas for how the government could change the rules to give union organizers access to independent contractors.

The unionists’ Plan A was widespread reclassification: using the government to say that people who traditionally did business as independent contractors would now suddenly be classified as unionizable employees. That’s the strategy the unionists implemented a half dozen years ago with California’s Assembly Bill 5, and it’s continuing most acutely right now with the proposed independent-contractor rule at New Jersey’s Department of Labor & Workforce Development.

And yet, while this Plan A strategy is still in motion, it hasn’t worked out the way the unionists hoped. Yes, they got Assembly Bill 5 into law in California, but what they initially called a landmark victory in that state has proved disastrous ever since—so much so that they couldn’t get the same kind of reclassification policy through in other states, or in Congress, before the evidence of serious harm to all kinds of independent contractors became clear for everyone to see.

Arguably, Plan A’s biggest achievement to date has been mobilizing the broader business community and independent contractors to join forces and fight back.

That’s what we’re seeing right now in New Jersey. The state Labor Department proposed an independent-contractor rule that attorneys say “almost entirely eviscerates” the ability to be self-employed and poses an “existential threat” to independent work. In response, an estimated 9,500 written opposition comments are on file, 99% of them opposing the proposal. We also testified 3-to-1 in opposition at a standing-room-only public hearing this past June, and gave additional testimony at a Senate Labor Committee hearing earlier this month. Everyone knows the State of New Jersey will face lawsuits if the Labor Department finalizes this rule proposal, with public comments like this one and this one and this one previewing the arguments attorneys could make in court. And legislators have already introduced concurrent resolutions in the state Senate and Assembly that would invalidate the rule, which is facing bipartisan concerns from two dozen legislators, including several committee chairmen and the Senate majority whip.

What’s happening in New Jersey is basically Newton’s Third Law of Motion coming to life over the reclassification strategy. The unionists try to push Plan A harder, and there is an equal and opposite reaction from all the rest of us.

Once a defense gets that strong—as any decent NFL team can tell you—it’s usually time to change the strategy if you still want to win the game.

In other words, it sure feels like time for the unionists to shift from Plan A to Plan B.

The Rise of Plan B

The 2018 report that the unionist members of Congress wrote states explicitly how Plan B would work. Under the heading “Explore Sectoral Bargaining,” the report’s authors detail how “the idea is to have industry-wide standards that are collectively bargained for across all employers.”

That’s sectoral bargaining. It’s a way for government to give unionists power over entire sectors of industry at once.

As I wrote about here, sectoral bargaining is different from the system of enterprise bargaining that has long been the norm for unions in the United States. With our current system of enterprise bargaining, union organizers go from business to business (from enterprise to enterprise) giving the employees at each business a vote on whether they wish to join a union. By contrast, with sectoral bargaining, that enterprise limitation is removed. Unions could set standards for entire industries at once, and those standards could affect independent contractors too.

One top lawyer called the way sectoral bargaining is coming into play right now unprecedented, raising questions about labor law, antitrust law and the U.S. Constitution’s Fourteenth Amendment.

The unionists themselves also acknowledge that a change to sectoral bargaining would be way beyond current norms. In that 2018 report, the authors wrote that sectoral bargaining “is admittedly radically different.”

But that fact didn’t stop the report’s authors from suggesting ways to get sectoral bargaining into law. To make this radical policy change happen, they suggested taking “an incremental approach, such as authorizing sectoral bargaining in one sector as a pilot program.”

That’s Plan B for independent-contractor policy. And even while Plan A is still happening, Plan B is already in motion, too.

Massachusetts, Minnesota and California

The Service Employees International Union—which wrote in spring 2024 about its goal to “win bold, groundbreaking sectoral organizing victories”—got its first big Plan B score in November 2024. A Massachusetts ballot initiative just barely squeaked through, at 54% of the vote, creating sectoral bargaining for rideshare drivers in that state.

As the union-friendly On Labor site reported, this was a “groundbreaking ballot initiative.” It was somewhat related to sectoral standard-setting models in the home care industry in Nevada, the nursing-home industry in Minnesota and the fast-food industry in California, but what happened with the Massachusetts rideshare ballot measure in November 2024 took Plan B a big leap beyond.

As On Labor wrote:

“Ensuring unions can bargain for all rideshare drivers to raise standards in the industry is a massive step forward and creates a potential model for other states to follow.”

That was the truth. The unionists’ intent was to create a model for other states to follow.

But most people reading the November 2024 news stories about Massachusetts would have had no idea that what was happening represented a radical shift in unionization policy that could, ultimately, spread not only to other states, but also to other industries as well. Headlines focused only on Uber and Lyft, because rideshare was the only industry immediately affected—just like in a limited pilot program.

What happened with the Massachusetts ballot measure was actually a win for union organizers looking to implement Plan B, but this is what readers were told instead:

After that, the SEIU moved to advance Plan B even further. In February 2025, legislation was introduced in Minnesota, where state Rep. Samakab Hussein—surrounded by people wearing SEIU scarves—said this:

“Big rideshare companies continue to do the bare minimum while making billions. It is time for change. This bill will give drivers the right to form a union and negotiate fair pay and protection … We are following the model that worked in Massachusetts. We will try to implement the same model right here in Minnesota.”

Now, to be clear, there was no sectoral-bargaining model that had worked in Massachusetts. There was a ballot measure that had squeaked through to make sectoral bargaining legal for rideshare drivers, with lawyers discussing whether it would hold up in court, and with Uber and Lyft saying they had concerns that they hoped the Massachusetts legislature could address.

Nevertheless, the Minnesota bill became a real thing, not just a theory—advancing the unionists’ Plan B. And similar to the Massachusetts ballot measure, the Minnesota bill wouldn’t even require a majority of rideshare drivers to agree before a union could end up representing all rideshare drivers in the state.

As the Minnesota Reformer reported:

“Under the proposal, if a union signs up 10% of eligible drivers, transportation network companies would have to turn over a list of drivers in Minnesota, with contact information. Then, if 25% of all drivers who’ve completed at least 100 rides in the previous three months sign up to join the union, it would become the exclusive representative in negotiating wages, benefits and working conditions.”

That bill is still in the works today, according to the Minnesota Legislature’s website, but a couple months ago, in October 2025, California leapfrogged ahead of Minnesota on helping the unionists to advance Plan B even more.

California Governor Gavin Newsom signed a sectoral-bargaining bill for rideshare drivers into law, with The New York Times describing the details like this:

“[If] 10 percent of California’s ride-share drivers indicate their support for a union through authorization forms, the union can file for an election to represent all of the state’s drivers. Alternatively, a union could be certified to represent drivers without an election by gathering support from a majority of drivers, or from 30 percent of drivers if no other group comes forward to demonstrate 30 percent support for challenging it.”

A union could be certified to represent all rideshare drivers in the state without an election, even with those drivers still classified as independent contractors.

That’s radically different, indeed, from union organizers being traditionally required to win a majority vote among employees at each individual company.

And that’s not all that changed with California signing the sectoral-bargaining bill into law. So did the media narrative.

It’s Not Fighting Misclassification. It’s Fighting Trump.

The sales pitch that the SEIU used to garner this win for Plan B in California was different from Massachusetts and Minnesota. In those earlier states, the SEIU had framed sectoral bargaining initiatives as a way to “win union rights” for rideshare drivers, following on years of claiming these drivers were misclassified employees.

But in California, the SEIU also framed the initiative as pushing back against President Trump.

It was a message crafted to appeal to a liberal-leaning electorate whose thinking, according to Pew Research Center, is already outside the norm on independent-contractor policy. Pew found that liberals are predisposed to believe that rideshare drivers in particular should be employees—something the majority of drivers themselves do not even believe.

Add a dash of anti-Trump sentiment to that liberal predisposition, and you get what Politico reported from California when the sectoral-bargaining bill made headlines in October 2025:

“SEIU California Executive Director Tia Orr painted the agreement as a sharp contrast to President Donald Trump’s recent threats to fire federal workers en masse amid a government shutdown in Washington.

“Trump is gutting workers’ fundamental right to come together and demand fair pay and treatment,” Orr said. “But here in California, we are sending a different message: when workers are empowered and valued, everyone wins. Shared prosperity starts with unions for all workers.”

That shift in narrative is significant in terms of what’s likely to happen next for us all.

We’ve seen this kind of language shift before, from the SEIU in particular as it tries to gin up support for targeting independent contractors. For a hot minute during the Kamala Harris presidential campaign, the SEIU stopped talking about “fighting employee misclassification” and started talking about giving independent contractors the “freedom to join a union.”

That language, based on the Harris campaign’s “freedom” theme, didn’t work very well for independent-contractor policy either, so in California a few months ago, it morphed again into “fighting President Trump.”

And that language shift, I must admit, has serious potential to work nationwide right now. Pushing back against President Trump is a theme in Democratic Party politics as a whole at the moment. It’s also a theme we’re seeing in my home state of New Jersey, with the incoming administration of Governor-elect Mikie Sherrill that is riding into power on a big liberal wave of anti-Trump sentiment.

Mixing sectoral bargaining into that same messaging would automatically get a lot of predisposed, liberal-leaning people to support it right now.

Quite possibly, in New Jersey next—and maybe in the next few months.

New Jersey S4898 and A6147

Out in California, there were actually two bills that Governor Gavin Newsom signed to give union organizers access to rideshare drivers through sectoral bargaining. As Politico reported in October, these two bills were a package deal that the SEIU worked out with Uber and Lyft.

Unionists got sectoral bargaining for rideshare drivers in the first bill, and then, in a second bill, Uber and Lyft got something they wanted: a way to “drastically reduce insurance coverage requirements for the ride-hailing companies.”

Politico wrote about that second bill:

“The second bill Newsom approved, SB 371 from state Sen. Christopher Cabaldon, slashes the amount of insurance coverage Uber and Lyft must carry for crashes caused by underinsured drivers from $1 million to $300,000 per incident.”

That language about underinsured drivers is why I noticed recently that New Jersey lawmakers had introduced Senate Bill 4898 and its identical companion bill, Assembly Bill 6147, here in my home state.

I posted about it on X on November 25:

It’s been a little more than a month since I posted that on X. The full text of the New Jersey legislation is now available.

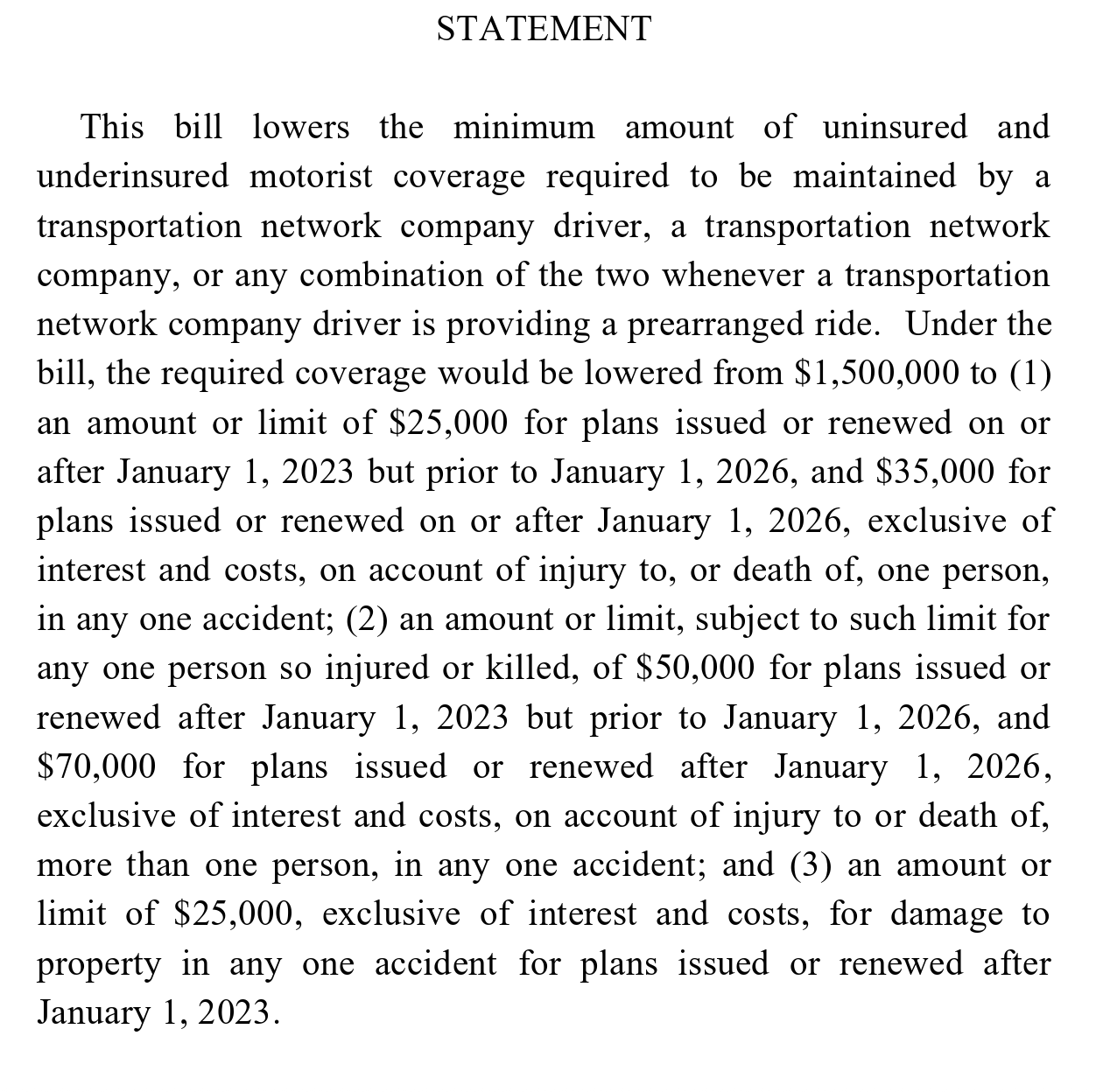

Here’s what it would do:

The words “independent contractor” appear nowhere in this New Jersey legislation. But the language in that descriptive statement still sounds an awful lot like a big piece of Plan B to me, based on what just happened in California.

And I’m no longer the only one who is talking about independent-contractor classification in relation to this insurance legislation.

The New Jersey AFL-CIO—which has long been a driving force behind Plan A and the widespread reclassification of independent contractors—issued a legislative advisory opposing the insurance legislation on December 12. This advisory makes crystal clear that the New Jersey AFL-CIO’s opposition is largely based on independent-contractor classification policy:

“Legislation (A-6147) seeking to drastically reduce (from $1.5 million to $100,000) the amount of uninsured and underinsured motorist insurance coverage required by a rideshare company and its drivers, such as Uber and Lyft, was recently introduced by Assemblyman Roy Freiman (D-16) and Sterley Stanley (D-18). The New Jersey State AFL-CIO is opposed to this bill because it would have a negative impact on drivers and passengers that are injured while using these services, but also because these companies continue to exploit their drivers by misclassifying them as independent contractors rather than employees.

“Misclassification strips away workers’ rights to numerous pro-worker protections such as unemployment insurance, workers compensation, minimum wage, overtime and the right to join a union, among others, simply to further increase corporate profits.

“Similar legislation passed in other states, such as California, has proven to be detrimental for consumers and drivers alike. For more information, please visit: California’s New Rideshare Insurance Law Shifts Risk From Uber to Passengers – Heimanson & Wolf, LLP.

“This legislation should not be considered until it properly protects consumers and drivers, as well as ensuring these ‘gig’ companies properly classify their drivers and give them the benefits they deserve and the right to join a union.”

That legislative advisory suggests the New Jersey AFL-CIO is sticking with the strategy of Plan A to reclassify independent contractors, while the SEIU is going around the country pushing for a switch to the strategy of Plan B and sectoral bargaining. News reports indicate that a similar thing happened in California. The California Labor Federation, AFL-CIO—led by Lorena Gonzalez, the former Assemblywoman who sponsored the reclassification law Assembly Bill 5—reportedly opposed the insurance bill that Governor Newsom signed into law as part of the sectoral-bargaining deal.

Here in New Jersey, Governor-elect Sherrill named leaders of both the AFL-CIO and the SEIU to her transition team in the area of “Jobs, Opportunity and Prosperity for All.” That means defenders of Plan A are very much still at the table.

But as I look at the current playing field, I think the SEIU has a better argument for shifting the strategy to Plan B.

How It Could (Pretty Darn Easily) Go Down

The massive statewide opposition to Plan A isn’t going anywhere in New Jersey. It only keeps growing as Governor Phil Murphy laughs out loud and generally appears to ignore the widespread opposition to independent-contractor reclassification.

But Governor Murphy’s remaining time in office is now less than a month. That presents a real opportunity for the Plan B squad on sectoral bargaining.

Even if the Murphy administration finalizes the Labor Department’s deeply misguided independent-contractor rule in the next few weeks, Governor-elect Sherrill could take office on January 20 and say something like: “I hear you, New Jersey independent contractors. I see your opposition to the Labor Department rule that my predecessor Phil Murphy put forward. My administration is going to move in a different direction.”

Sherrill could then sign the insurance legislation into law—meaning half the California deal, done in New Jersey too—with the table set to add the other half of the deal in a sectoral bargaining bill.

California’s lawmakers even created a playbook for how Governor-elect Sherrill could sell this whole deal to the public as part of her affordability agenda. California state Senator Cabaldon described bill number two—the bill that cut insurance costs for Uber and Lyft—like this in his press release:

It’s not about reducing insurance costs for Uber and Lyft. It’s about improving affordability for everyday people.

That press release includes this quote:

“I am incredibly grateful for Governor Newsom’s commitment to addressing affordability and lowering the costs of rides,” Senator Cabaldon said. “My interest in carrying this legislation was to lower fares for people who use rideshare for necessary transportation to their jobs, school, or medical appointments. …”

Strip out the name of Governor Newsom, insert the name of Governor Sherrill, and you would have the affordability agenda moving forward by implementing sectoral bargaining in New Jersey, right out of the gate with the new Sherrill administration.

And from There, the Whole Country

If that all turns out to be what happens next, then it’s easy to see Plan B making its way to Congress and the whole rest of the country.

The unionists would have the concept of sectoral bargaining on the books in three of the bluest states: Massachusetts, California and New Jersey. And as Reason noted, some high-powered Republicans in Washington, D.C., just may be willing to join them in attempting to spread the concept nationwide:

“This could even become a bipartisan push. Given Republicans like Vice President J.D. Vance and Sen. Josh Hawley (R–Mo.) embracing organized labor, others on the right could be moved to support gig worker unionization.”

Reason’s writer is correct. I have written much the same thing. There’s a small but powerful faction in today’s Republican Party that, like the SEIU, has been flirting with this sectoral bargaining strategy to empower unions for quite some time now.

I wrote a while back:

“On the other side of the aisle, where Republicans have traditionally stood squarely on the side of protecting independent contractors, newly nominated vice presidential candidate JD Vance seems to think sectoral organizing is a good idea, too. He’s talked about it more than once. Conservative think tank guys like Oren Cass are working hard in Washington, D.C., right now to spread this idea of ‘pro-worker conservatism.’”

So, it may turn out that I was right on the money with that July 2024 article, whose title was, “We Need To Talk About Sectoral Organizing: Freelance busters are eerily enthusiastic about this idea, which they think they can achieve without reclassifying independent contractors as employees.”

Or, you know, maybe not. And maybe what I’m suggesting here at the end of 2025 won’t happen in New Jersey, either.

Like I wrote at the top, it’s a bit dicey to offer predictions. Anything could happen. Even the Pro Bowl kickers sometimes have really bad days.

Certainly, I don’t think anybody would have bet on the AFL-CIO being even remotely in agreement with yours truly on anything involving independent-contractor policy as we close out the year 2025. And of course, if this Plan B strategy comes to pass in 2026, we’re also going to see lawyers descend on all these states and in the federal courts to challenge the concept of sectoral bargaining on the whole, right up to the U.S. Supreme Court. Whether the concept will stand in the long run is an entirely other question.

But for now, when I look across the whole playing field, I see a lot of signs that the unionists who want to switch to Plan B and sectoral bargaining are in a stronger position than the ones still embracing the Plan A reclassification strategy.

We’re all just going to have to keep our eyes on the ball as we head into the new year together.