The Fascinating Footnotes

In its public comments about New Jersey's independent-contractor rule, the Workplace Justice Lab cites several studies worth a closer look.

New Jersey’s Department of Labor & Workforce Development received an estimated 9,500 public comments about its proposed independent-contractor rule, with 99% of the comments opposed. On the supportive side, two of the couple dozen comments are from the same source: the Workplace Justice Lab at the Rutgers University School of Management and Labor Relations.

One of these two comments is from Jake Barnes, who is research project manager at the Workplace Justice Lab. He states in his June email to the Labor Department that he is writing to correct verbal testimony he gave at the public hearing that month, and adds: “We also plan to submit more extensive written comments before the August deadline.”

The other comment is that August submission from the Workplace Justice Lab itself. It’s filed by Melanie Stratton Lopez, senior attorney for strategic enforcement.

As you can see if you read them, these two submissions are largely the same, at just a few pages apiece. The most significant difference is that in the August submission, the Workplace Justice Lab adds this new paragraph toward the end of the comment:

“To the extent that certain commenters argue that some independent contractors will be transformed into employees under the proposed regulation, we note that this proposed regulation codifies existing New Jersey common law, which already articulates the ABC test. Such fears are overblown: either these businesses have been out of compliance, or they are in compliance with existing common law, and these regulations will not have a substantive impact on their business structure.”

That’s a notable extra paragraph. It appears to contradict what New Jersey’s Labor Department itself states, which is that the proposed rule-making would (emphasis mine): “codify the NJDOL’s interpretation of the ABC test for independent contractor status.”

This extra paragraph also begs the question of why, if nothing is going to change, there would be any need for this rule-making in the first place.

Still, I read through the Workplace Justice Lab public comments to try and understand their perspective. I’m glad I did, because what I found surprised me, particularly in the footnotes.

Universities vs. Unions

The Workplace Justice Lab comments include a number of citations that are all too familiar from the freelance-busting brigade. Among them are the 2009 Government Accountability Office report that cites data as old as 1984; and the 2025 Economic Policy Institute research that’s based on a bunch of that union-backed think tank’s estimates.

But there are also some unusual footnotes in these comments. And the research in unusual footnotes is always worth a look, since New Jersey’s Labor Department could use the arguments from any public comments to help determine what happens next.

The first such citation that I dug into goes with the following claim in the Workplace Justice Lab comments:

“A 2022 Berkeley Labor Center study noted that between 12.4 percent to 20.5 percent of the U.S. construction workforce was either misclassified as contractors or paid off-the-books.”

That’s how the research is presented in the body of the public comments, as if the research comes from Berkeley Labor Center, which is affiliated with the University of California Berkeley.

The footnote, however, makes clear that the data actually originates in this 2020 study, whose title page presents its authors as academic researchers from other higher-education institutions.

If you read down to page nine of this 2020 study, you can see the supporting organizations for this commissioned research: a carpenters’ union and an organization called ICERES.

And then, page 10 makes clear that two of the study’s three authors, in addition to being affiliated with universities, are also the president and former president of ICERES, while the third author is a former executive secretary-treasurer of the New England Regional Council of Carpenters.

ICERES has numerous people tied to unions on its board of directors. Scott Littlehale is executive research analyst at the Nor Cal Carpenters Union, while Chris Trahan Cain is director of safety and health for North America’s Building Trades Unions, the umbrella organization also known as the Building and Construction Trades Department, AFL-CIO. The executive director of ICERES is Julie Brockman, who has been affiliated with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers and the International Union of Painters and Allied Trades.

You can decide for yourself whether it is reasonable for the body of the Workplace Justice Lab public comments to describe data from this 2020 research as being from a 2022 Berkeley Labor Center study, or whether it should have perhaps been identified as union-backed research.

In addition, you can decide for yourself whether this 2020 research should be used as a basis for any policymaking about worker misclassification at all, given this caveat that its authors included on page 40 about their own findings:

“Before concluding the section, it must be noted that this study makes no claim about the relative size of off-the-books employment versus worker misclassification in these results. The data simply does not allow for definitive classification of workers into either of these two groups. While it is tempting to consider those who claim to be employed despite not showing up on company payrolls as ‘misclassified workers,’ the 2002 report by an analyst at the U.S. Census Bureau revealed that these individuals also feature a large number of off-the-books workers. While conversations with industry stakeholders have consistently suggested that off-the-books employment dwarfs worker misclassification, the lack of distinction between the two types of workers in the data leaves us without sufficient empirical standing to evaluate these claims.”

Workplace Justice Lab vs. Workplace Justice Lab

Another old chestnut that the freelance busters like—the statistic that 10% to 30% of employers misclassify people as independent contractors, from the 25-year-old Planmatics study—kicks off the following paragraph in the Workplace Justice Lab comments.

It’s a long paragraph, and I’m going to break it down here into two parts. This is the first part of that paragraph from the Jake Barnes comment:

“Between 10–30% of employers nationally misclassify at least some of their workforce as ‘independent contractors.’ A 2022 Berkeley Labor Center study noted that between 12.4 percent to 20.5 percent of the U.S. construction workforce was either misclassified as contractors or paid off-the-books. The Economic Policy Institute has found that independent contractors in New Jersey across 11 occupations that are often misclassified lose between 19% and 37% of their total compensation compared with W-2 employees.”

So far in this paragraph, we have the antiquated Planmatics citation, the 2022 Berkeley citation that’s actually from a union-backed study, and the Economic Policy Institute study based on a bunch of estimates from that union-backed think tank.

But here’s where things get really interesting. This very long paragraph—that is ostensibly about misclassification—continues by stating this:

“Vulnerable workers, like those paid close to the minimum wage floor, like home health aides, construction workers, and janitors, are most susceptible to minimum wage violations. And, minimum wage violations hurt low-wage workers the most. In 2022, the Workplace Justice Lab found that New Jersey workers paid below minimum wage lost on average $1.62/hour—about 20% of the legal minimum wage. I don’t know about you, but I can’t afford to leave 20% of my paycheck on the table each week. Luckily, this rule will help deter the misclassification of employees and, in turn, help put that 20% back in workers’ pockets.”

So the paragraph starts by talking about misclassification, and ends by talking about misclassification.

In between, the Workplace Justice Lab folks included a citation that’s new to me, about 2022 Workplace Justice Lab research and the minimum wage.

It refers to this 2022 report by Daniel J. Galvin, Janice Fine and Jenn Round of the Workplace Justice Lab. And that report does, indeed, state the exact thing that’s in the Workplace Justice Lab public comments, about how New Jersey workers paid below minimum wage lost on average $1.62/hour—about 20% of the legal minimum wage.

But stating that $1.62 is 20% of the minimum wage sounded wrong to me, so I looked it up. According to the State of New Jersey, the minimum wage was $13 an hour for most employees as of January 1, 2022. That means $1.62 would’ve been about 12%, not about 20%, of the legal minimum wage in that year.

After I realized that, I dug deeper into the 2022 Workplace Justice Lab research. The more interesting find, for the purposes of the New Jersey Labor Department’s proposed independent-contractor rule, is that this 2022 Workplace Justice Lab research is actually based largely on data from New Jersey’s Labor Department itself.

Now, it’s not all recent data. The first page of this Workplace Justice Lab research states that while the report is dated 2022, some of the data is as old as 2009. But still, the two types of data that form the basis of this research are described like this:

Underlying violation rates are estimated using Current Population Survey Merged Outgoing Rotation Group data

Complaints data are supplied by the New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development Division of Wage and Hour Compliance

Combining this data, the authors didn’t find anything remotely like 10% to 30% of employers misclassifying at least some of their workforce as independent contractors. In fact, this 2022 Workplace Justice Lab research doesn’t include the terms “independent contractor” or “misclassification” at all.

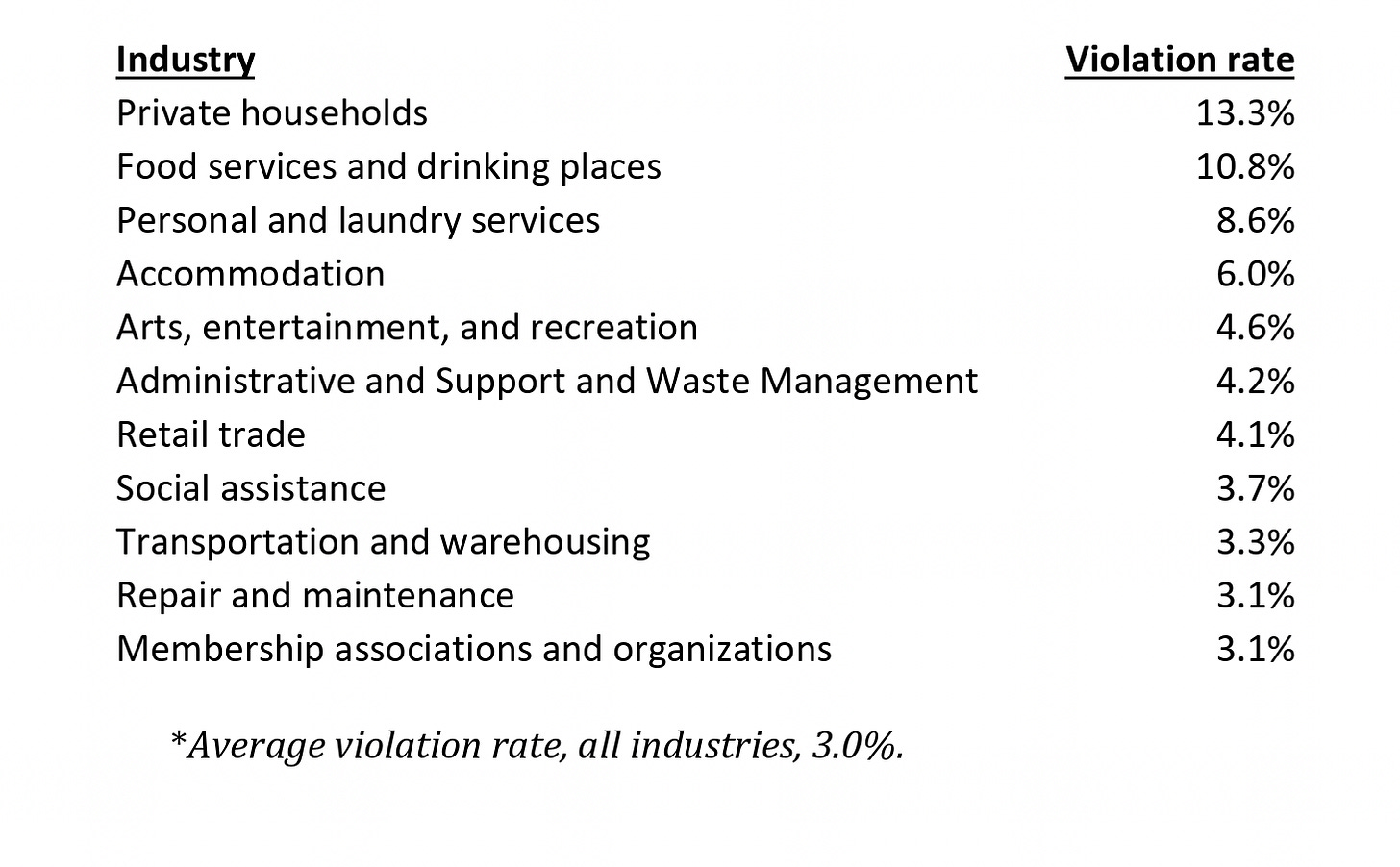

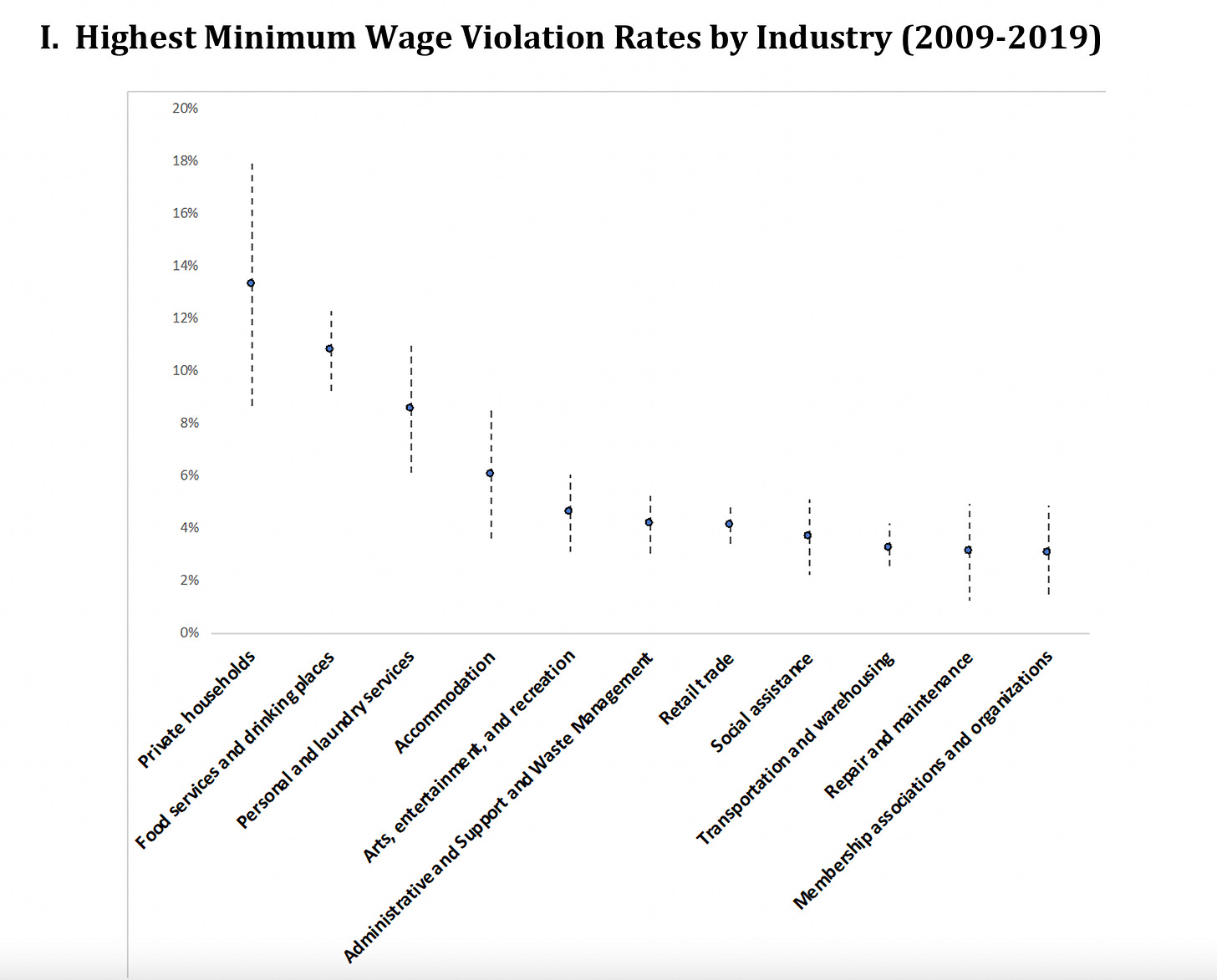

Instead, what this 2022 Workplace Justice Lab research found—research that is, again, based largely on data from New Jersey’s Labor Department—is that there is an average minimum-wage violation rate of just 3% across all industries.

Now, even if we did give these Workplace Justice Lab public comments the benefit of the doubt, and even if we all agreed that minimum-wage violations are the same as employee misclassification (which they’re not), an average violation rate of 3% is a lot different than claiming an across-the-board misclassification rate of 10% to 30%.

And on top of that, the most significant minimum-wage violation rates this 2022 Workplace Justice Lab research found weren’t occurring at companies, but instead in private households, specifically with regard to individuals employed as maids and child-care workers:

As I kept reading, I realized this 2022 Workplace Justice Lab research also seems to contradict another bit that’s in the Workplace Justice Lab public comments.

The comments state:

“Vulnerable workers, like those paid close to the minimum wage floor, like home health aides, construction workers, and janitors, are most susceptible to minimum wage violations.”

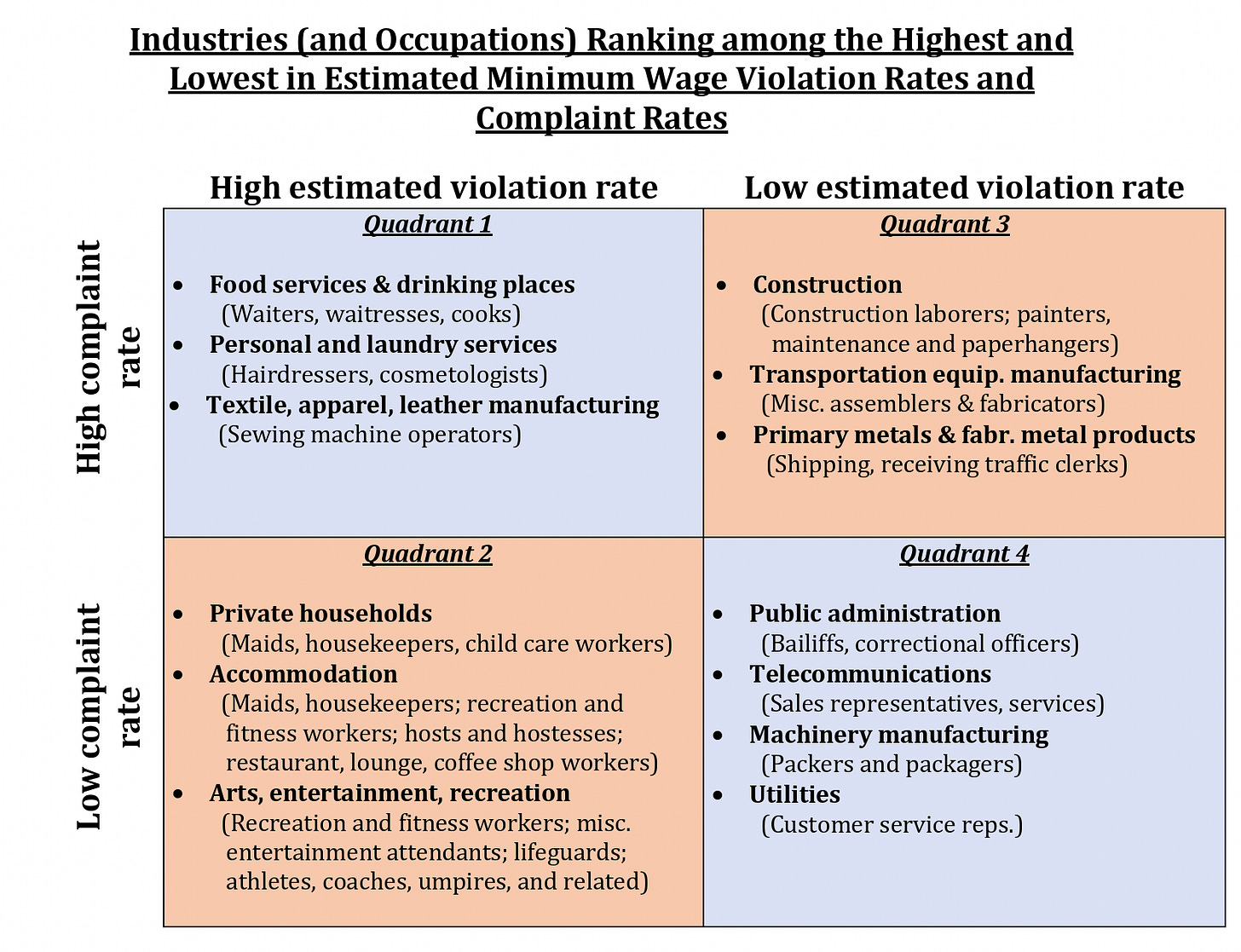

But the 2022 study by the Workplace Justice Lab specifically lists construction laborers as being in an industry where people file a lot of complaints, yet there are actually a low estimated rate of actual violations.

They even made a handy-dandy color-coded chart:

To be clear about what that chart shows, the authors of the 2022 Workplace Justice Lab study wrote:

“Industries in Quadrant 3—construction, transportation and equipment manufacturing, and primary metals and fabricated metal products—yield many ‘false positives,’ meaning that the rate of minimum wage complaints received by the NJ DOL WHD significantly outstrips the estimated rate of violations in those industries. Violations in these industries are relatively rare, but workers in these industries tend to be highly ‘vocal.’ This means that NJ DOLWHD’s resources may be inefficiently allocated to investigating complaints in these industries.”

In other words, while the Workplace Justice Lab public comments say construction workers are “most susceptible” to minimum-wage violations, the Workplace Justice Lab research says such violations in the construction industry are “relatively rare.”

All of which would be fascinating enough on its own, but what’s most notable to me about this 2022 Workplace Justice Lab research is the wording in its own title and conclusion.

Remember: The entire point of the Workplace Justice Lab public comments is to express support for the Labor Department’s proposed independent-contractor rule—which is sweeping in nature, targeting all industries with no exemptions, and affecting every conceivable type of independent contractor in the state.

By contrast, the title of the 2022 Workplace Justice Lab report is: “Minimum Wage Violations in New Jersey: Toward Strategic Enforcement.” The 2022 report’s conclusion does not call on policymakers to enact any sweeping interpretation or broad rule-making whatsoever with regard to independent contractors.

Instead, the authors of the 2022 Workplace Justice Lab research conclude this:

“It is our hope that these results may help inform a strategic enforcement program within New Jersey.”

Calling for strategic enforcement of minimum-wage violations is not the same as calling for the kind of rule-making that New Jersey’s Labor Department has proposed, or that these public comments are supposed to be about.

Which brings us, finally, to this passage near the end of the Workplace Justice Lab public comments:

“Adding regulatory clarity will also allow the NJ Department of Workforce Development to streamline its investigations because it will not have to waste valuable and finite resources proving that workers are employees subject to the state’s laws. Instead, the regulations will presume coverage and the employer will have to show otherwise.”

Yes, the Workplace Justice Lab is arguing here that the proposed rule-making would allow the Labor Department to presume everyone in the state is an employee.

While that extra paragraph the Workplace Justice Lab added in its August comment argues that fears are “overblown” about the rule-making transforming independent contractors into employees.

Like I said, the research in unusual footnotes is always worth a look, because New Jersey’s Labor Department could use the arguments from any public comments to help determine what happens next.

As one of New Jersey’s estimated 1.7 million independent contractors, I sure hope the Labor Department is reading as carefully as the rest of us are.

Great investigating, Kim. Super good!