The Individual

When I read this comment supporting New Jersey's proposed rule, I suspected it was an AI fake. I was right, and I was wrong. Reality complicates everything.

An estimated 9,500 written public comments were filed about New Jersey’s proposed independent-contractor rule, with the comments overall being 99% opposed. I’m aware of only 26 comments in favor of the rulemaking. Eighteen of those supportive comments came from organizations, while the remaining eight came from individuals.

This article that I posted last week covered the last of the comments filed by organizations.

Today, let’s look at the eight individual comments, five of which are quite short:

Those short comments are typical for this kind of process. They sound like something a real person would fire off in a text or email.

Two more of the eight individual comments also seem real to me. They’re longer, but each one has a tone and content that seem appropriate for how the people describe themselves:

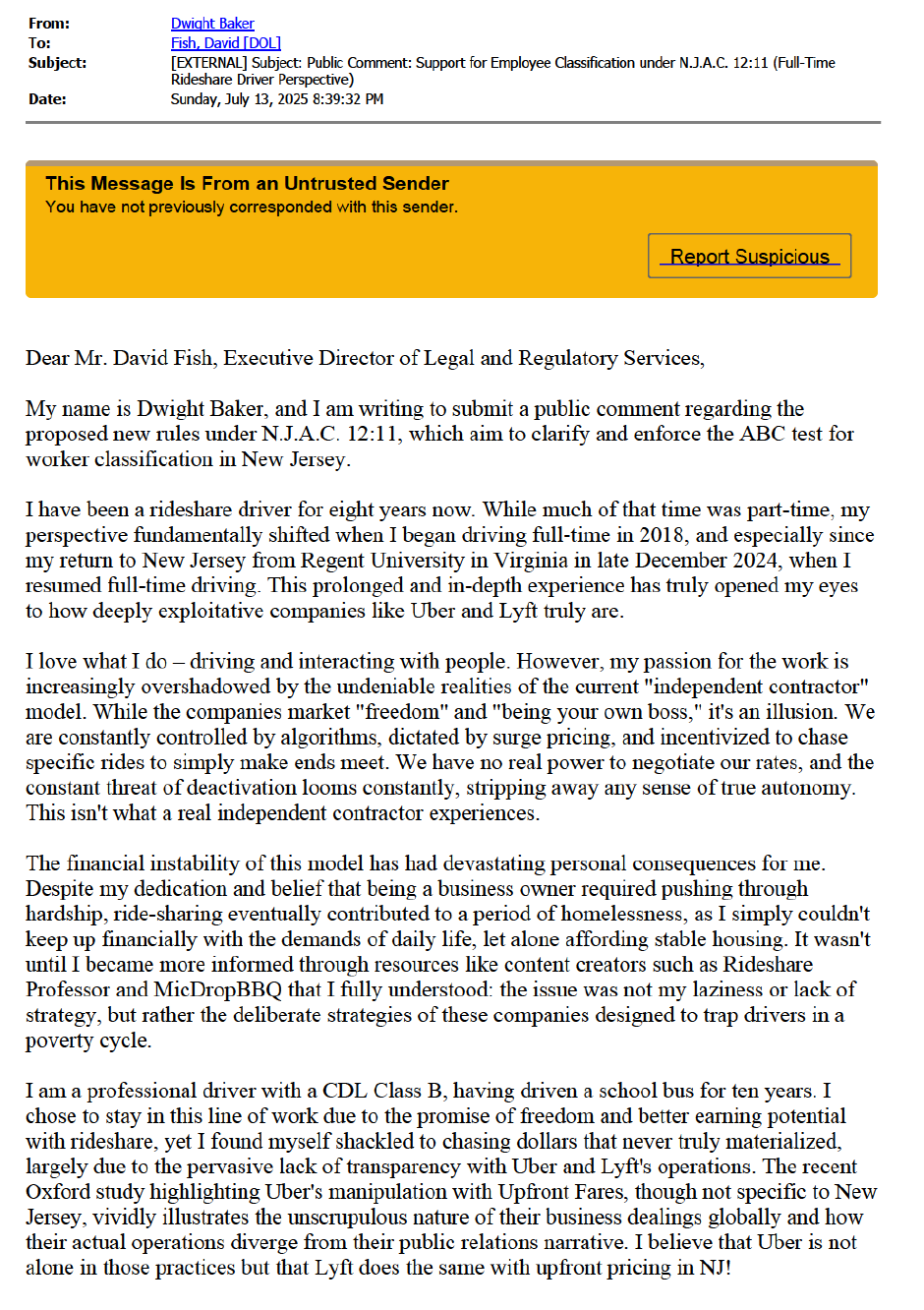

But then, there is the last of the eight individual comments filed with New Jersey’s Labor Department.

This comment is signed by a person named Dwight Baker—and it has an entirely other structure and tone.

When I read this public comment, I immediately suspected it was an AI creation.

It’s polished, blending personal hardship with legal and policy arguments. It’s written with the kind of rhetorical escalation you might expect in a political speech or congressional testimony—tension that increases until the end, where there’s a strategically placed moral call to action. There’s a five-section structure with an introduction, personal story, industry critique, policy stance and closing.

Everyday people don’t tend to write this way.

My next question was whether Dwight Baker was even a real person at all.

‘Why Can’t They Differentiate?”

So, I called Dwight Baker. Lo and behold, he called me back.

I introduced myself as a writer who has been covering what’s in all these public comments. I told him that his comment stood out to me because it was, by far, the most detailed comment that any individual filed in support of New Jersey’s proposed rule.

He seemed surprised. I said his comment was so well-written, I thought it might have been an AI-generated fake.

“I hate writing,” Baker told me. “I didn’t—well, it’s true, but I didn’t write it. I wrote it with the assistance of AI. I let AI write it, and then I changed a lot of the language. It was robotic. I didn’t like it. For me, I used AI to get the ball rolling.

“Everything in there is absolutely true, and it’s my thoughts,” he added. “I hate writing. It’s why I couldn’t finish college.”

He then generously gave me about a half hour for a phone interview, before he had to get to work. After talking with him, I believe he’s sincere. He doesn’t know the specifics behind everything in his public comment—“Did I quote from an Oxford University study? Maybe I saw a YouTube video about that”—but he clearly is a person who has thought about his experiences with various app-based companies. He wants their business practices to change.

Baker told me he’s 36, unmarried with no kids, and living in his sister’s basement. He drives about 30 hours a week for the same school-bus company he’s worked with on and off for about a decade. He returned to New Jersey less than a year ago, in December 2024, after attempting to earn a degree at Regent University in Virginia. It’s a Christian school. He chose it, he said, because he believes God has called him to become a pastor.

“I still do Uber on the side, but it’s just getting harder and harder,” he told me. “And it’s not just Uber or the gig economy. The whole world, minority countries, first-class countries, it’s all about greed. The way to remove the worker bee is to replace them with machinery or AI. Then they don’t have to pay people.”

Since his public comment says gig workers should be treated as employees as soon as possible, I asked him why he thought becoming an employee of Uber would improve his situation.

“Nobody who drives Uber wants to be an employee of Uber,” he told me. “You’re supposed to be an independent contractor. There’s three things I love about Uber and gig work. The flexibility—I can turn it on anytime I want. And I love dealing with people. Schoolkids, I love them. I love people, and I love driving. The biggest problem is the pay. The pay is not fixed. When I started Uber and Lyft in 2017, I was under the impression that they got a fixed percentage.”

What he was telling me seemed to contradict what’s in his public comment. I asked him again whether he actually wanted to be an employee of Uber.

“I wouldn’t mind being an employee of Uber if it works around my school bus schedule,” he said. “But I don’t know how that would work for them. How much would they have to change in order to employ me? And I don’t think that’s in Uber’s business plan.”

He told me he’d prefer a system where rideshare companies paid drivers 20% to 25% of the fares that customers are charged. Right now, he said, he believes the companies are auctioning off rides and seeing how little they can pay the drivers.

I asked him why, if he believes rideshare companies are treating drivers unfairly, he doesn’t do something different. Maybe take a part-time or full-time job at a local store.

“Driving the school bus, the schedule, I never know exactly what’s going to happen,” he said. “Today, I’m probably going to get back at 5 or 5:15. I can’t make it back for a job with a shift that starts at 4 o’clock, and if I’m working at night, that interferes with driving the school bus first thing in the morning.”

Again, he said, a good setup for him would be continuing to drive for the rideshare companies, but for more income.

“I think the solution should be they get a fixed percentage, and that’s it,” he said. “It’s all about money. That’s what it comes down to at the end of the day. I would like to have my own transportation business, but it costs too much money.” He itemized some of the startup costs: commercial insurance, registration fees. “I don’t have $25,000 to do that.”

Again, this sounded different to me than what’s in his public comment. Instead of saying he wanted to become an employee of Uber, he was now saying his preference was to be his own boss, entirely off the apps.

He told me he has come to realize, with time, that the apps are taking advantage not just of him, but of everyone who drives for them.

“Uber and Lyft thrive on ignorance and desperation. It’s terrible,” he said. “Technically, our schedule is flexible, but if you actually want to make money, there are certain times and certain places where you’re going to make more money. You’re driving Fridays and Saturdays, driving in the cities.”

He said he uses an app called GigU that tells him what he’s earning after expenses. “What they’re offering drivers in Jersey is criminal,” he said. “These requests are under $20 an hour gross. What does that net? A few dollars an hour? I want to see Uber and Lyft kicked out of New Jersey.”

He added, “I actually enjoy Uber. I meet so many people, and I learn so much, but my car doesn’t ride on air.” He talked about needing to pay for gas and for repairs after having to get towed out of Philadelphia a week ago. “Uber doesn’t care. They’re not paying for that.”

I asked him if he had tried other apps, since he seems to like driving so much.

“I’ve done Doordash on the side,” he said. “I think all the gig companies should be kicked out of New Jersey. They should be kicked out of the country. They’re taking advantage of people who don’t know any better.”

He told me that if he’s going to be an independent contractor, he should be treated like one. “Why am I not able to negotiate rates?” he asked. “My only ability is to accept or decline. I wish they gave us a certain percentage. Uber and Lyft are playing with the books.”

He also told me he has “a lot of issues,” but in the end, “I just want to see the right thing done. The rich rule over the poor, and the rich people ultimately write the rules.”

As for the proposed rule in New Jersey, he said, “I’m not worried which way it goes because the God of the Bible is ultimately the judge, and they can’t avoid him. I believe God is going to provide.”

And he reiterated, again, that what he really wants is to be a pastor.

“I want to shepherd God’s people,” he said. “That’s why I went to the university, for Christian ministry.” I asked if he could become a pastor without a degree. He said, “A lot of churches want a degree. They want a man who is married with children, and I don’t have any of that.

“Many churches are lost in the love of money,” he added. “That’s why you have all the megachurches.”

We talked about how app-based drivers aren’t the only types of independent contractors who would be affected if New Jersey finalizes its proposed rule. We talked about attorneys, nurses and freelance writers, including me. We talked about how some independent contractors earn a good living, and about how all of us probably agree that groceries cost way too much these days.

“There’s different types of independent contractors,” he said. “Why can’t they differentiate the types of independent contractors?”

That’s a good question, I said, adding that the thing we all have in common is that we’re all independent contractors. That’s why so many people from all kinds of professions filed so many public comments about the proposed rule.

He thought for a moment before responding: “I think what they all have in common is that they need to get paid.”

A Lot of Issues, Indeed

There’s a lot to consider after that phone call, including whether the AI-generated public comment that Dwight Baker filed is actually representative of what he thinks.

On one level, I believe it is. He doesn’t like the way app-based companies are doing business, and he wants to see that change.

However, on another level, the answer is no. During our phone interview, he suggested numerous possible solutions to the problem he has identified, including app companies paying drivers more, or him starting his own business.

I didn’t ask what he meant when he said he has “a lot of issues,” and I don’t know anything about his life other than what he told me. I did wonder whether he’d feel so frustrated about his future prospects if he had succeeded in his Christian ministry studies last year.

It also seemed to me than in a state that spends millions of dollars promoting the idea of upskilling and training, we should have a program within our Department of Labor & Workforce Development that can identify a guy like Dwight Baker based on a public comment like this one. He might be able to earn good money with the kind of AI proficiency he demonstrated, if there’s a program or service that can point him in the right direction.

And of course, in the interest of fairness, it’s also important to consider what the companies he mentioned have to say for themselves. Here is the public comment that the Flex Association—the “voice of the app-based economy”—filed in New Jersey. It directly addresses some of the issues that Dwight Baker raised:

“Flex is opposed to the Department’s proposed new rules as they would dramatically reduce opportunities for independent work and in doing so, cause tremendous harm to the state’s economy and residents,” this comment states. “The proposed rules are misaligned with the realities of 21st-century independent work and represent the nation’s most extreme approach to date with respect to worker classification policy.”

The Simple Days of Alexander Dolowitz

And speaking of things going to extremes, Dwight Baker’s AI-generated comment also raises a lot of questions about the public-comment process itself.

While this comment didn’t turn out to be wholly fake, it is accurate to describe it as being AI-enhanced in a way that masks a fuller picture of reality. That’s an augmentation of the problem Congress has been working on for a while now, with legislation intended to ferret out fake comments. These submissions are a problem that is far from new. Back in 2017, a Wall Street Journal analysis revealed a federal comment process being flooded with fakes.

We also saw fake comments during the federal rulemaking about independent-contractor policy a few years ago. As just on example, somebody calling himself Alexander Dolowitz filed 44 public comments, sometimes saying he lived in Salt Lake City, Utah, or Murray, Utah. And his email address sometimes changed from comment to comment too:

The differences between the Alexander Dolowitz comment at the federal level and the AI-generated comment in New Jersey are depth and specificity.

As you can see above, the Alexander Dolowitz comments were filed in November 2022. That’s the same month ChatGPT was first released to the public. AI systems like it weren’t yet widely used. Back in those olden tech days of three years ago, this was how a fake comment looked:

Since then, we’ve all watched technology like ChatGPT get better at simulating human-generated text. When I fed Dwight Baker’s comment into Grok, it told me today’s AI could have generated it with a prompt as simple as this:

Write a 2-page NJDOL public comment from Dwight Baker (West Deptford, ex-Regent U, CDL driver, homeless due to Uber) supporting ABC test reclassification. Cite Rideshare Professor & Oxford study, show conflict over IC status, end with Yahoo Mail footer.

This time, it turned out to be a real person writing the AI prompts.

What happens next time—and how it could affect public policymaking for us all—is an entirely other conversation.